Nathan Arthur (aka narthur, of TaskRatchet fame and who we’re now proud to also have on the Bee Team part-time) had such an amazing response to some Beeminder skepticism in a forum thread about Beeminder vs CBT that we asked him to blog about it. The backstory is that sometimes people accuse Beeminder of being a crutch or self-blackmail or suggest that more positive approaches should be better. A common candidate for “more positive approaches” is Cognitive Behavorial Therapy, which Nathan is well-versed in. So, without further ado…

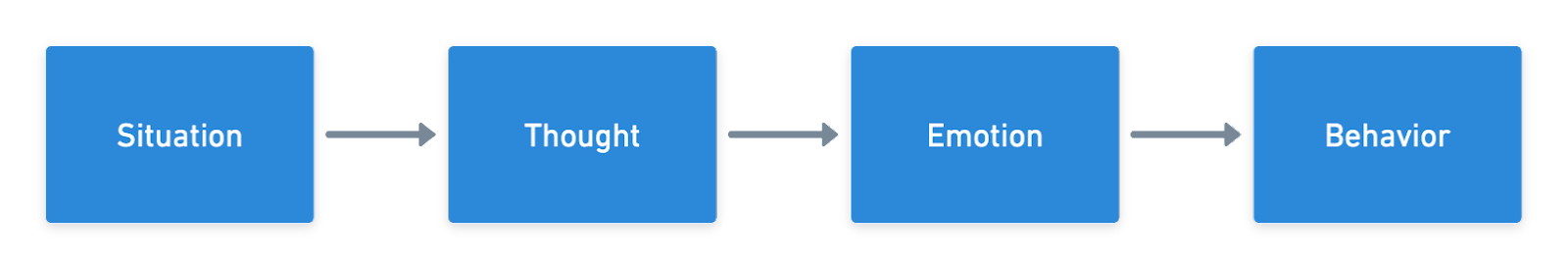

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is all the rage. (See, for example, Scott Alexander’s excellent primer on CBT as a part of his article on depression.) To explain it, let’s start with a crude cognitive model of human behavior: our behavior is the result of our emotional state which, in turn, is created by the thoughts and beliefs we hold about our situation.

The anti-Beeminder view takes that model and claims that the best way to change your behavior is to address your thoughts, rather than trying to change your actions directly. If you leave your thoughts unchanged, you’re likely to continue dealing with the same behavioral problems. If you change your thoughts, behavior modification is automatic. It’s the difference between repeatedly cutting the top off of a weed and pulling it up by the roots.

This objection paints Beeminder as an inefficient and needlessly-stressful game of behavioral whack-a-mole — that it’s a superficial fix that leaves the source of the problems unaddressed. Wouldn’t we rather address the underlying thoughts and emotions that give rise to the behaviors rather than Beeminder’s approach of just changing the behaviors?

We could try to sidestep the objection by instead beeminding the root issues. But Beeminder works best for concrete, quantifiable, controllable metrics. Thoughts and emotions are none of those things. So instead we beemind behaviors — getting to bed on time, doing our chores, spending less time on Facebook.

And it’s worse than that, says our hypothetical Beeminder naysayer. Providing a superficial fix for an internal problem enables denial of the deeper issues. Without Beeminder, I would be forced to address the real issues — my distorted thoughts and beliefs. Therefore, I should actively avoid Beeminder and similar tools in order to ensure I do the hard work of addressing the root causes!

What CBT Actually Says

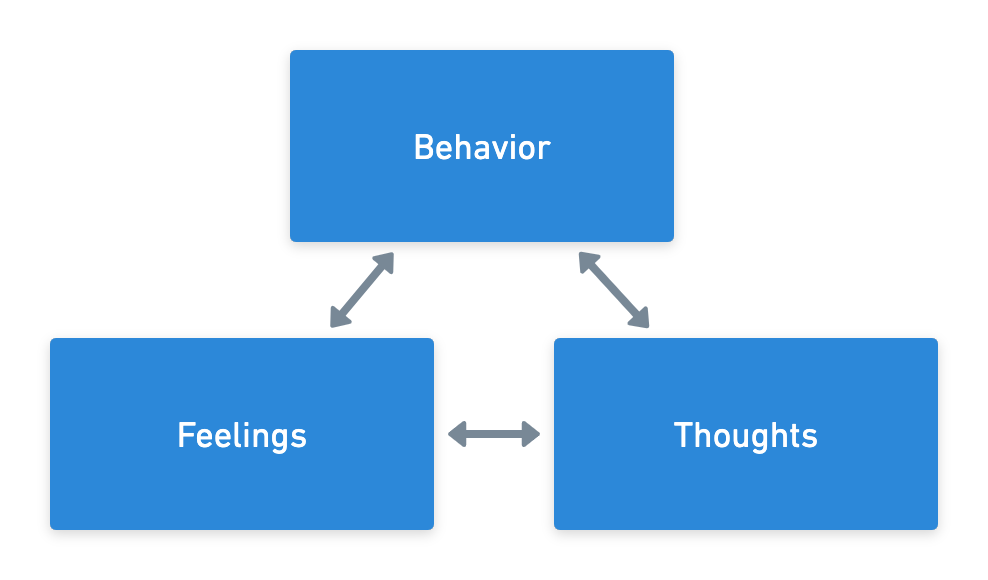

The error in that logic is the one-way causal connection between what one thinks and feels and the resulting behavior. This isn’t what CBT teaches. CBT states that our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors are tightly interconnected, each influencing the others in an open feedback loop.

Each node in the triangle can impact, and be impacted by, any other node. Notice that our behavior has a direct impact on our thoughts and feelings. “Fake it ‘til you make it” contains a grain of truth.

| Thought | Feeling | Behavior | |

| Thought | — | I think that there’s no way I can succeed, therefore I feel sad. | I think that my boss will be upset if I’m late for work, therefore I start getting ready to leave. |

| Feeling | I feel angry, therefore I think that someone must have wronged me. | — | I feel happy, therefore I smile at someone on the street. |

| Behavior | I do a favor for someone, therefore I think that I must like this person. | I turn on my favorite song, therefore I feel energized. | — |

Beeminder and Identity

Beyond thought and emotion, tools such as Beeminder can help us to change our self-perceptions by allowing us to implement habits, which, in turn, provide evidence of our new identities. James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, is a proponent of this idea. According to Clear, behaviors, habitually repeated, form our identities.

The opposite of this effect is learned helplessness. If we’ve experienced repeated failure in a certain area, that failure can become a part of our identity. We have learned that we are helpless to make progress toward this goal, so we stop trying.

Learned helplessness can sneak up on us when we’re trying to reinvent ourselves. If I want to become a programmer, I may decide to start spending time learning how to code. For a few days I may succeed in doing that. But then I start hitting more challenging topics. It gets frustrating. And then an unexpected event comes up and I skip a day. And soon I’ve given up the goal entirely. I’ll likely be hesitant to make another attempt in the future, remembering how helpless I felt the last time I tried.

Beeminder is an incredible tool for moving from learned helplessness to conscious competence. Instead of relying on my willpower, I’m able to create an external commitment that will keep me on track. Each day I meet my goal, I’m creating evidence that I can become a programmer. And eventually I’ll have enough evidence that I will begin to think of myself as a programmer. Programming will have become a part of my identity.

And even if I derail, having a Beeminder goal guards against slipping into learned helplessness. Beeminder puts my past progress front-and-center with its cumulative graphs. I can visually see all the time I’ve already spent learning to program — the evidence is right there, regardless of my recent derailment. And the fact that my Beeminder goal is still there, ready to get me back on track after a short break, creates the implicit assumption that I still have what it takes to get back up and keep going towards my goal. It’s subtly hinting that I should view myself as a person capable of growth in the face of setbacks.

My Experience with Beeminder and CBT

I’ve been seeing a CBT therapist for some time now. Beeminder has been key to that therapy’s effectiveness for me. Anxiety, depression, and ADHD — the very problems I needed my therapist’s help to address — prevented me from implementing the interventions they recommended. Beeminder bridged that gap by giving me an external system I could lean on to help me make the changes I needed to make. And it helped me to stick to those changes long enough for them to start having an effect.

For example, my therapist recommended that I keep a thought journal, recording my negative thoughts and challenging them in the moment. But without any salient reminder to do this between sessions, I inevitably never did. A simple do-more Beeminder goal fixed this by regularly prompting me to watch for negative thoughts to address.

And the Winner Is…

Both! The point is, CBT and Beeminder aren’t in competition at all. Using Beeminder alongside CBT can produce better results than either alone. If you’re seeing a CBT therapist, Beeminder can help you implement the therapy. If you’re not, it’s still worth using CBT’s ideas. Beeminder-driven behavior change can bootstrap deeper changes in cognition, emotion, and identity.